Remembering Nyerere in Tanzania

History, Memory, Legacy

Review by: Gavin Macarthur, Tanzania Affairs

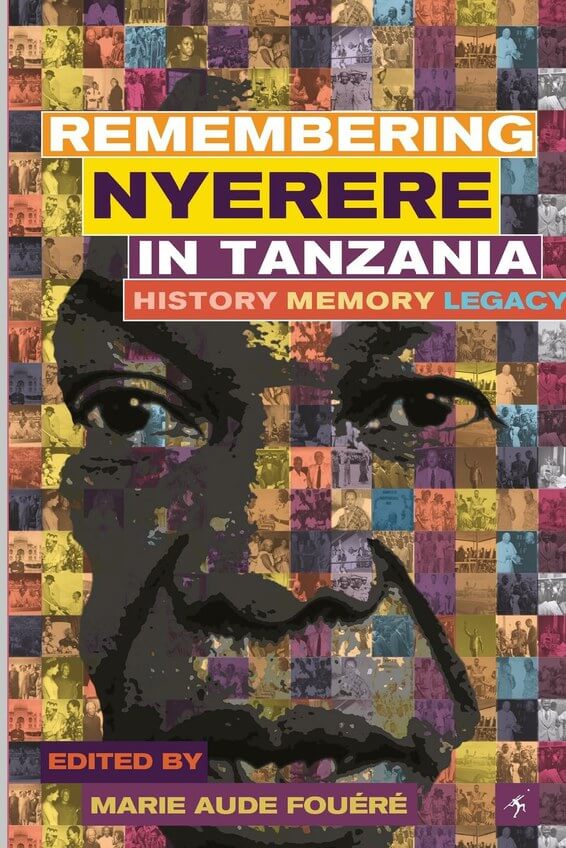

Remembering Nyerere in Tanzania. History, Memory, Legacy

Edited by Marie-Aude Fouéré

I enjoy edited volumes on a particular theme or topic for three reasons: first, they sometimes include excellent work by previously unpublished researchers, edited by scholars with specialised knowledge of the theme or topic; second, they are a useful forum for established authors to account for this emerging scholarship in their own treatments; and third, read together, the bibliographies attached to each essay serve as an excellent cross-referencing tool to guide further research.

This collection is a good example of such a publication, gathering together a good deal of new research from emerging scholars on the topic of remembering Julius Nyerere, Tanzania’s first president. Keen to develop a new perspective on this topic, the contributors’ essays explain their collective determination to break from an enduring scholarly tradition of valorising Nyerere, his political works and his significance in the history of African democracy. As Marie-Aude Fouéré points out, the essays she has edited in this volume focus instead on the production of a usable past for a contemporary (re)imagination of nationhood, in which ‘Nyerere’ becomes a ‘floating signifier’, that is, an unfixed political metaphor that is deployed in different ways in the course of debating and acting upon the present.

Many of the chapters in the book document and discuss this issue as it applies to Nyerere and his works. For example, Emma Hunter’s chapter suggests how the Arusha Declaration and Ujamaa were Nyerere’s way of winning back political power for himself and his party by formalising a pervasive anticapitalist and anti-corruption discourse in post-colonial Tanzania. Despite the failure of Ujamaa as a socioeconomic model for prosperity and equality, the policy allowed Nyerere to cement his reputation as an incorruptible figure of righteousness and social justice and, following his death, allowed others to transform him into a contemporary symbol of a more moral time in the past.

The essays by Kelly Askew, James Brennan and Mary Ann Mhina are all to some degree concerned with what might have been or might still be concealed or occluded by Nyerere’s shadow as it figures in literary, academic and poetic engagements with him in his guise as the hardworking, modest, self-effacing schoolteacher and as the august and preeminent torch-bearer of Tanzanian – and African – political self-determination and independence. After all, we must wonder about the reasoning behind Nyerere’s decision to establish a foundation named for himself that, according to Olivier Provini’s chapter, pays him a permanent tribute by disseminating his political thought through various media and the publication of his speeches.

In her chapter, Mhina points out that our view of discourse – and the signifiers and symbols it deploys – must not neglect the ability people have to perpetrate, penetrate, transcend or ignore it, depending on context and their own particular needs. Fouéré extends this point, explaining that whoever and whatever Nyerere the man might have been during his lifetime, the signifier/symbol called ‘Nyerere’ has become a polyvalent means of both operating upon the past in the present and of deploying the past in operations upon the present. Individual and corporate efforts to claim Nyerere in this fashion are also telling: those who vie for power over Nyerere’s meaning do so in the knowledge that their particular signifier can, through the power of the symbol, become a mirror that reflects the virtues they ascribe to it back upon them. If the signifier/symbol they have created is powerful and widely accepted, they may, by associating or affiliating with their symbol, draw upon its power to legitimate their own authority and projects.

The chapters by Aikande Kwayu and Kristin Phillips, for example, each present research data to explain how political legitimacy is appropriated by those who can present themselves as lineal descendants of whatever politically expedient version of Nyerere they successfully posit, while Provini and Sonia Languille consider how Nyerere’s educational legacy is honoured or ignored in the administraton of contemporary university and secondary education.

The essays in this book all touch on what I see as a particularly Tanzanian syllogism: Nyerere was all that was best about Tanzania in the

past, while Tanzania remains all that its greatest son made it. Whether the conclusion of this logical expression is true or not, I expect

that this volume is only the beginning of a much deeper study of the symbolic power of Nyerere-asmetonym-for-Tanzania, as well as a more

wide-ranging consideration of his significance(s) in East Africa and further afield.

Gavin Macarthur

Gavin Macarthur graduated with a PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Manchester in 2009. His doctoral research suggests that the islands of Zanzibar are imagined in multiple cultured modes, continuously resituating the Isles in differential historical, geographical and socio-political relations with the Tanzanian mainland and other places around the globe. He is currently developing a health-focused eco-adventure tourism project to implement certain of the UN’s sustainable development goals in Jeju island, South Korea.