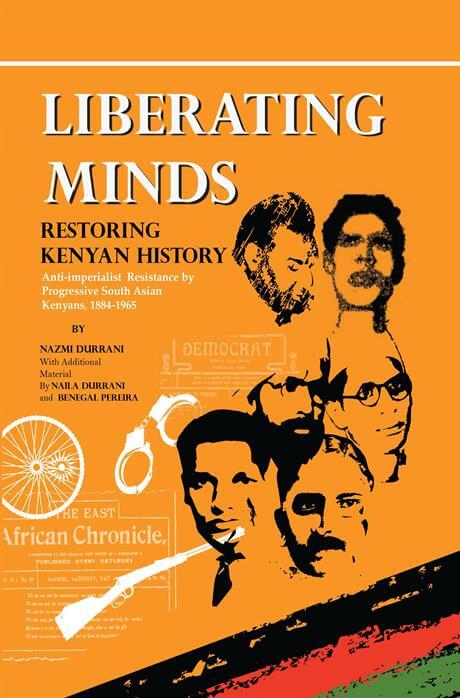

Liberating Minds, Restoring Kenyan History

Review by: Ramnik Shah, Opinion

Liberating Minds, Restoring Kenyan History

Nazmi Durrani

The message of this book is that against colonial oppression there was resistance, and `Liberating Minds` were the voices of activists and others who opposed British rule in Kenya.

This represented a strand of history that has been selectively pieced together and documented here. The raison d'être of the work however is Nazmi Durrani, and it is his considered writings about them that form the main thrust of the narrative, supplemented with biographical notes about his own background and trajectory. These point to his `transition from a left-leaning intellectual to a political activist` within a relatively short timescale from the end of the 1970s to his untimely death on July 1, 1990 at the age of 48. It was during this period that he wrote purposefully in original Gujarati, and some in Kiswahili. Readers of Opinion may recall the series of his Biographies of Progressive South Asian Kenyans which appeared on this forum last year (2016). These are now republished yet again, with English translations.

What we learn is that Nazmi chose to write in Gujarati and publish his articles in a non-mainstream magazine, Alakmalak (અલકમલક), to escape Kenya`s post-colonial state censorship, a fate that had befallen his brother [Shiraz] who “had been hounded out” of there by government agents for writing about one of those (progressive) heroes that he, Nazmi, had been researching and recording, namely Pio Gama Pinto. Alakmalak was a minority outlet and so he also wrote poems and other material in Kiswahili in order “to reach the majority of the working classes in Kenya.”

In the first part of the book are set out Nazmi`s Biographies of Progressive South Asian Kenyans: Manilal A Desai (1878-1926), Makhan Singh (1913-1973), Ambubhai Patel (1919-1977), Pio Gama Pinto (1927-1965) et al; a chapter on Patriotic Kenyans: Journalists, Editors, Publishers, Printers (in three parts); and a review of the 1977 film Moolu Manek (મુલુમાણેક) – all in Gujarati followed by English translations. Next is a five-page section entitled `Remembering Heroes and their Achievements` with pictorial graphics, reprinted from a previous book by Shiraz Durrani.

Then, under the rubric `South Asian Kenyan Resistance in Historical Context`, comes the longest single piece, spread over 27 pages: Naila Durrani`s 1987 paper `South Asian Kenya Participation in People`s Resistance`, originally prepared for presentation to a conference of Kenyan overseas political organisations which came together in London to form a united front aligned to the underground Mwakenya-December Twelve Movement dedicated to fight the authoritarian regime of President Moi. This was a wide-ranging discourse in which, among other things, she traced the evolution of the Kenya Asian working class in conflict with the exploitative powerhouses of the big British financiers and industrialists of the early colonial period into a successful and upwardly mobile bourgeoisie of petty traders, merchants, technicians and professionals who, though in the past had played a pivotal role in the fight against imperial rule, aiding and joining hands with their indigenous African counterparts, nevertheless have at different points since during the journey “been exposed to double oppression as a class and as a minority nationality far removed from their land of origin” and who “often seek protection by looking up to the few, very rich members of the upper and the middle petty bourgeois Asian Kenyans.” Her focus however was on the historical class basis of the conflict between ruler and subject, going back to the building of the railway and the influence of the worldwide anticolonial Ghadar movement that had spurred its followers in Kenya to resort to revolutionary activity during WWI resulting in imprisonment and death sentences for some of them. She also discussed the rise and role of the progressive Asian stalwarts mentioned above.

Other chapters follow in a similar vein, with a mix of articles by Nazmi extracted from Alakmalak with English translations and what appears to be an original piece in English, `Background to Class Formation and Class Struggle`, followed by `An Introductory Reader` on `Kenya`s Fight for Freedom`, also by him.

The next item featured in this section of the book is a most fascinating and revelatory contribution by Benegal Pereira about the `Life and Times of Eddie H Pereira (1915-1995)`, his father, whom he justly and proudly describes in the title as `Indian Nationalist Extraordinaire in Kenya`. Eddie was a fiercely anti-colonial Kenya Indian Goan patriot, who was born in Mombasa in 1915, in the middle of WWI. As Benegal writes: “He lived through a still greater war, and more significantly, witnessed the end of colonialism in both India and Kenya and the rise of these new nations from their more or less bloody births and their memories of ancient splendours”. His passion to fight for freedom and equality was inspired by his time in India as a student during the 1930s at the height of the nationalist movement, and so when he returned to Kenya, fired up by Gandhian ideals, he began to make his opposition to colonial rule vocal in whatever way he could. He became famous for his feisty and fearlessly expressed letters to newspapers in which he castigated not only the white ruling class and structure of government but also his fellow Goans for siding with the imperialists and for their Portuguese-Indian split psyche and pretensions. He always boldly signed off these letters with `Jai Hind`. He wore traditional Indian clothes made of khadi and sported a white Gandhi cap, and his profile in that attire adorns the chapter and makes a stunning impression. He had attained such notoriety and so offended the authorities as to be hauled before a court on a trumped up charge (which was more in the nature of a civil wrong than a criminal act) and sentenced to a term of six months` imprisonment. A number of these letters have been reproduced in the book. These, under such headings as `These Whites`, `Equality for Goans`, `Goans` Unity` and his contemptuous dismissal of `Portuguese Metroplitan Status for Goa`, stand as proof of the ferocity of his views. He was, alas, murdered in Nairobi on January 25, 1995, and the case has remained unsolved to date. As Benegal informs us, he left behind the manuscripts of three unfinished books: one was to be his autobiography, while the other two were entitled `A Trail Blazer Century: The History of Indians in Kenya` and `Goans in Kenya: A New Breed.` These he is hoping to publish in due course.

The next section, headed `Nazmi Durrani: Biographical Notes`, contains a mixture of reflections on Nazmi`s life and career by several of his friends and (again) his brother Shiraz, together with a poem by and other literary references to Nazmi`s work. The book concludes with an explanatory introduction to the Index, pointing to the rationale for identification of the key figures listed in there.

But despite the fact that the book bears the imprimatur of a Foreword by our own Vipoolbhai Kalyani, and that it has been well received at public launches in Nairobi, I am afraid a few words of friendly criticism are in order and hopefully will be taken in that spirit.

First, the book`s fourfold long title lacks any reference to it having been edited by anyone. It is implicit in the very nature of the collection and its presentation that the work is the product of an editorial enterprise and the person responsible for it appears to be Shiraz Durrani, perhaps with the assistance of a or more than one member of the Durrani clan! Why not therefore say so? There are also, alas, several editorial flaws in the book. The significance of the dates 1884-1965 in the subtitle is not readily apparent. Admittedly Pio Pinto was assassinated in 1965, but the addition of Eddie Pereira prolongs the time span to 1995. More importantly, the listing in the Index of many names (some of which are misspelt, as is Makhan Singh`s name in Gujarati at page 35) does not correspond with the actual pagination, and the same applies to items under Contents – no doubt this could be due to a failure of coordination at the print stage! There is also much repetitive retracing of Nazmi`s life and career in Shiraz`s Preface and Highlights of an Activist`s Life, and some chapter classifications could have been better arranged or signposted. That said, other aspects – details of publication, acknowledgements etc – and the Gujarati/English content and format generally do give a wholesome and professional touch to the book.

The life-stories of the progressive anti-imperialists of the main title have been the subject of countless articles, books and other literature and are familiar to the older breed of Kenya Asians, whether resident or in diaspora. To that extent, there is nothing new in the restatement of their respective contributions to the struggle for freedom and equality in Kenya (and the inclusion of Eddie Pereira is a welcome addition). The value of the book is really as a record of one man`s valiant attempt to put or interpret that history in the wider context of class politics - namely that of Nazmi Durrani, to whom it also partly serves as a biographical tribute, buttressed by his like-minded friends and family - and as an educational tool for the present younger and future generations of all Kenyans worldwide.

Ramnik Shah © 2017

http://opinionmagazine.co.uk/details/2677/-liberating-minds--restoring-kenyan-history