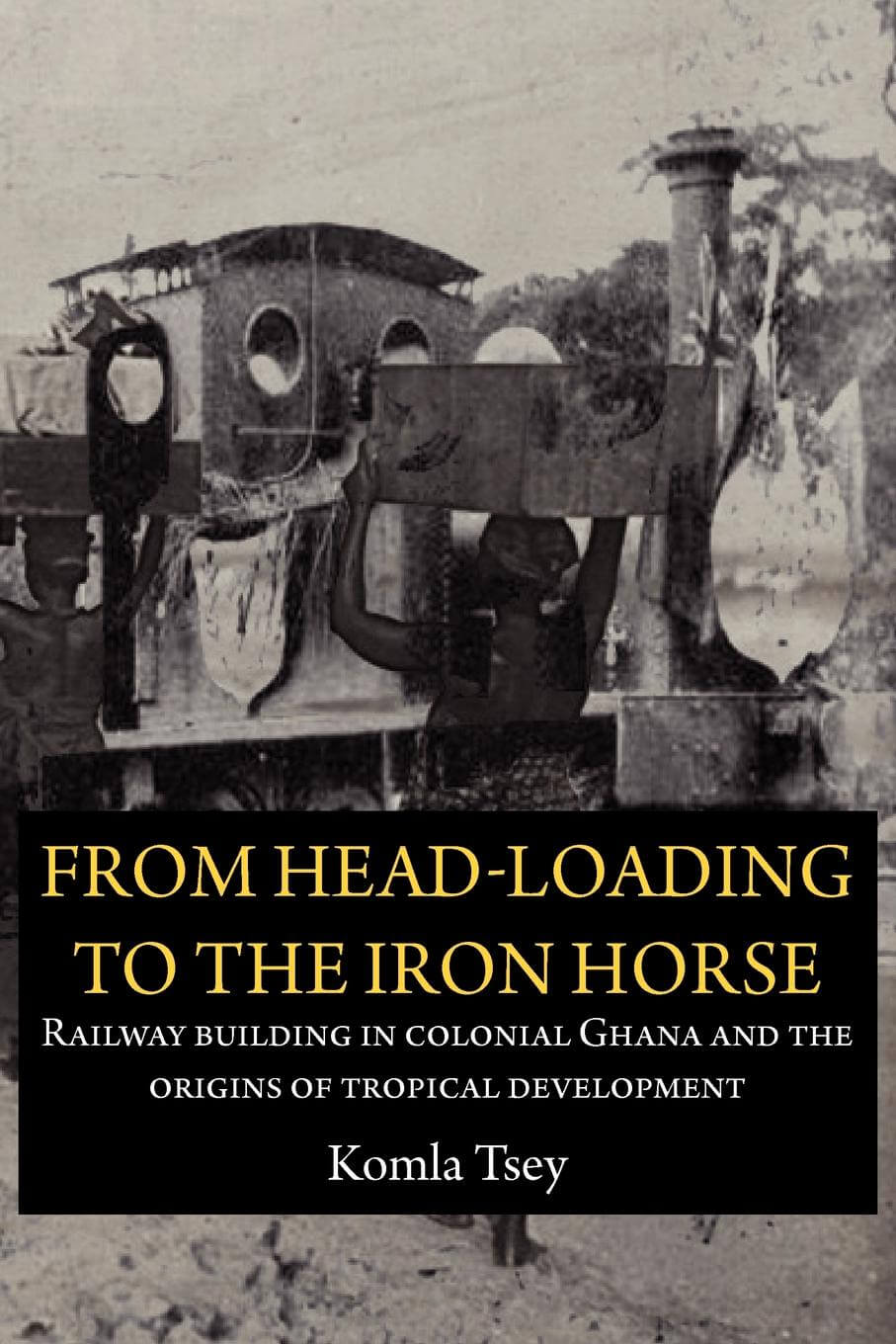

From Head-Loading to the Iron Horse

Railway Building in Colonial Ghana and the Origins of Tropical Development

Review by: African Studies Bulletin, University of Leeds

From Head-Loading to the Iron Horse

Komla Tsey

While excited talk of regenerating the railways in West Africa surfaces from time to time, the colonial legacy of the ‘iron road’ has generally got a bad press in West Africa.

Playgoers attending performances of Wole Soyinka’s Lion and the Jewel watch the (white) surveyor accepting a bribe from the wily

Baroka to divert the railway-line and leave the Bale in control of Ilujinle, and readers of Ayi Kwei Armah’s Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet

Born encounter

a railway system in which corruption is rife.

In his study based on a thorough investigation of colonial papers, minutes, memoranda, correspondence, and gazettes, Komla Tsey points to the historic roots of this tradition of corruption. The British engineers working in the Gold Coast put colonial interests and self-interest first; they got away with botched jobs and skull-duggery.

One of the most telling episodes Tsey describes concerns the building of Takoradi harbour – for obvious reasons railways and harbours were habitually hitched in the colonial context. After drawing attention to the escalating costs of the contract for the construction of the harbour, Tsey refers to the withdrawal of the company that had won the contract, Stewart and McDonnell. It seems that Rendel, Palmer and Irriton were then appointed consulting engineers and the work itself ‘was tendered and was won by Sir Robert McAlpine and Son.’ That firm, and it may be remembered the founder was nicknamed ‘Concrete Bob’, undertook to finish the contract ahead of schedule and negotiated a ‘bonus system’ with the Crown agents. By this, McAlpine would receive £1,500 for each week that the project was completed before December 1930.

Tsey reports that the harbour was handed over a full twenty months ahead of schedule and the appropriate (huge) bonus was paid (52). However, it soon became ‘apparent that a number of the cylinders on which the wharves rested were seriously defective, “being filled with rubble instead of concrete, and cracking at water-level over a distance of 190 feet”’. Tsey quotes Colonial Office memoranda of 7/9/1928 and 13/12/1930 that refer to evidence of ‘hurried work’ and ‘sharp practice’, and he notes that, despite this, ‘McAlpine did not forfeit the bonus’. Such arrangements and outcomes were, Tsey shows, all too common in the British Empire in relation to railways (and harbours) and it is clear that Ghanaians do not have to cite the Tanganyika Ground-nut scheme when looking for an example of incompetence and self-interest masquerading as ‘tropical development’.

In twelve chapters of crisp, clear prose, Tsey lays out the extent to which the railways (and harbours) in the Gold Coast benefited Britain, its manufacturing base, its engineers, and, even, since engines in the Gold Coast ran on British coal, its miners.

The story of the book itself also repays examination. In reading From Head-Loading to the Iron Horse and when following up the footnotes, I was struck by how few of the sources were recent. Tsey does not date the journal articles he cites, but, from the books in his bibliography, it is apparent that the work for this volume was done and pretty well dusted by about 1985. Digging a little more deeply into the origin of the work, I discovered that the volume is based on a PhD thesis presented to the University of Glasgow by Tsey, then ‘Christian Tsey’, in 1986. I also found that Glasgow has a welcome, Twenty-First Century readiness to make research submitted to them available on-line. Unlike many theses, this one has worn well. This is a challenging, fundamental slice of economic history that should be studied by all involved in ‘tropical development’. Tsey remarks that the story he has to tell could only be excavated because of the scrupulous imperial record-keeping. This prompts a despairing glance at the desperate state of Ghana’s National Archives and raises questions about whether future historians will be able to uncover uncomfortable truths about current ‘development projects’? If they can’t, we may have to rely on playwrights and novelists, the heirs of Soyinka and Armah, for warnings about cheating, chicanery, deceit, deception, dishonesty, double-dealing, and duplicity – to go no further than ‘d’ in the scammers’ alphabet of sharp-practice.

Reviewed by: James Gibbs, University of the West of England.

[Published in Leeds African Studies Bulletin 75 (Winter 2013/14), pp. 95-96]