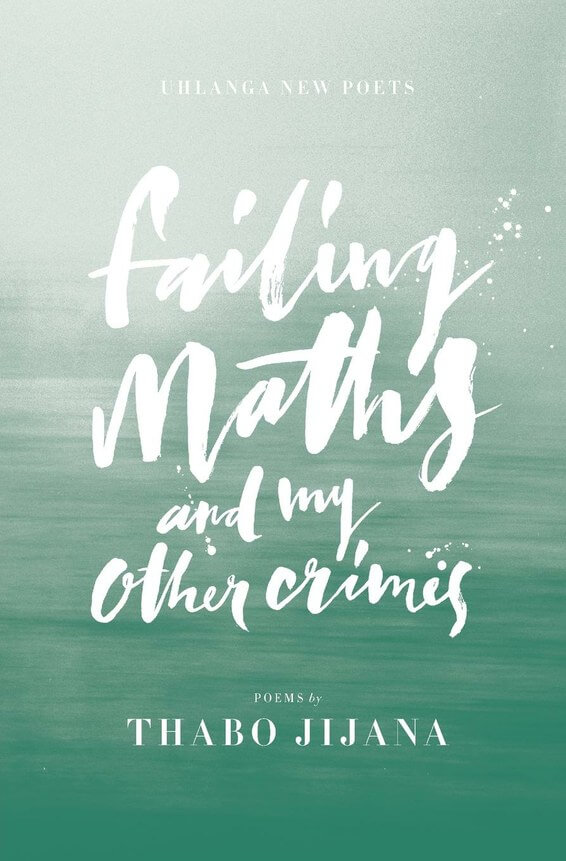

Failing Maths and My Other Crimes

Review by: City Press, South Africa

Failing Maths and My Other Crimes

Thabo Jijana

You can only be one of the uHlanga New Poets once, it seems. Published by Nick Mulgrew, who offers his own poems here, the series is intended to collect and publish the first collections of South Africa’s most promising young talents, who will hopefully go on to greater things.

That makes little books like these a precious record and a tacit encouragement of thoughtful verse in a world in which poetry (and increasingly literature itself) struggles to matter as much as it once did.

I’m told there was once a halcyon time when poets were more famous than people who make badly lit sex tapes and marry rappers who never let you finish your acceptance speech. But such a time is hard to imagine now.

Hopefully, uHlanga continues and helps to support a culture of poetry among a generation of introspecting youth. There’s a lot to like about the collections by Genna Gardini, Thabo Jijana and the 25-year-old publisher Mulgrew.

Gardini pulls you in with confessional accounts of her experiences (or vicarious imaginings) of body-shaming, homosexuality, depression, abuse, desire and a potpourri of memories from different stages of her life. Much of it is heartbreaking and discomfiting, and will haunt you afterwards.

Jijana, too, gets under your skin, particularly the poem The thing about Manto and beetroot, where the narrator is waiting for a man, presumably his father, to walk in the door “stinking of engine fumes, the/ sleeves of his corduroy shirt/ rolled up to the elbow, his hands/ caked with oil”. In the end, you realise that’s not going to happen because, beside the kraal, “there is now a dune/ of red soil and a white cross;/ the black paint washed away, nothing as clean as a name”.

Jijana offers a mix of small observations of township life with deeper meditations on history, culture and personal angst. In his poem about the murder of Steve Biko in police custody, he keeps the free verse minimalistic – because he knows the event has already been sermonised upon countless times. By simply ending with “alone/ he lay on/ the stone floor/ alone”, he locates the personal tragedy of it better than a more grandiose or sweeping verse might have done (and it ties in with “a black man, he/ was on his own”, a play on some of Biko’s own, famous words).

Mulgrew’s poems are more quirky and playful, charmingly often at his own expense, such as his admission at the discomfort he felt at being assumed gay by a stranger, when he isn’t. In many ways, his poems are diary entries about experiences, thoughts, small lessons and wry satire at the absurdity of contemporary society.

He pokes fun at things like armchair activism, self-deprecates his own relative privilege and, in the title poem, pokes holes in the idea that all of humanity is somehow complicit in its own destruction. No, he points out, “some of us are more/ at fault than others” … because “some people don’t/ drive V8s in cities or comment on News24/ or racially abuse people at beer festivals or/ picket gay marriages obviously”.

On the strictly technical side, there’s a part of me that’s still a bit old school when it comes to poems. I want them to feel like poetry, to have more rhythm, metre and clearly discernible structure; to use more figures of speech, more imagery and more metaphor (and yes, horror of horrors, maybe even the occasional rhyme).

Gardini does this most often, and Jijana is also at his best when his poems fall into a discernible rhythm. At times, some of the verse can come across more like prose broken up into lines and labelled poetry. All the same, the collections seem to work. These young poets should have bright futures as writers in whichever form they turn their hands to. On a day when a 70-year-old version of one of them wins a Nobel prize, people will start to look frantically for first editions of little books like these from decades before.