Drinking from the Cosmic Gourd

Review by: Sanya Osha, The Johannesburg Review of Books

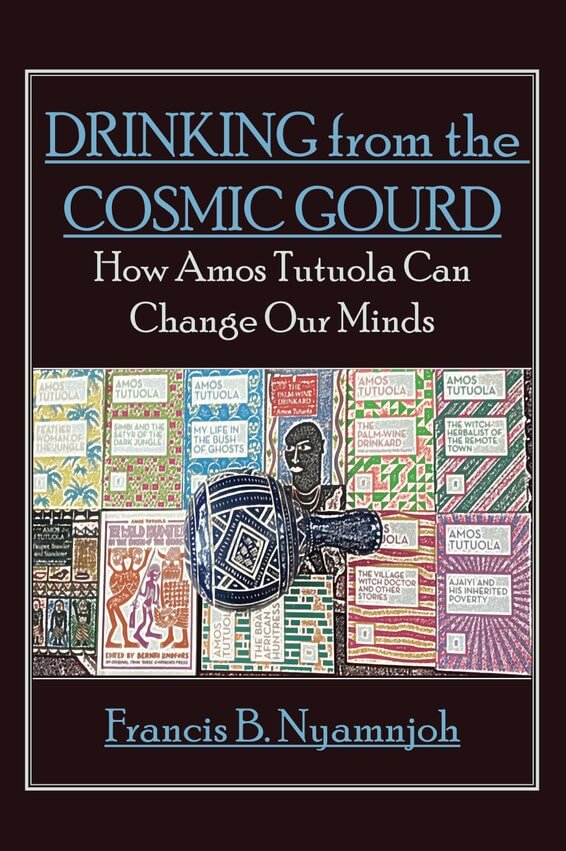

Drinking from the Cosmic Gourd: How Amos Tutuola Can Change our Minds

Francis Nyamnjoh

Amos Tutuola deserves contemplation as a writer independent of the clutches of anthropology, argues Sanya Osha. How can we foster such a critical approach?

The quirky title of Brian Eno and David Byrne’s 1981 avant-funk album My Life in the Bush of Ghostscomes from the most unexpected of sources: Amos Tutuola’s 1954 novel of the same name.

1. This obscure homage is perhaps more intriguing than Dylan Thomas’s famous, generally complimentary review of The Palm-Wine Drinkard: ‘brief, thronged, grisly and bewitching’. Thomas, that pivotal British post-war figure, embraced poetry in a whole-hearted, unconscious, even elemental way. Eno and Byrne, by contrast—especially in their most well-known collaboration, The Talking Heads—seem more ambivalent about the power of their medium of choice, and their status as ‘famous musicians’. In this, their position was similar to Tutuola’s, who downplayed his literary artistry, eschewed Dylan-like ‘man of letters’ machismo, and displayed a kind of passive-aggressiveness toward audiences that arose from the shifting critical ground under his feet.

Because of his uneasy relationship with Literature-with-a-capital-L, one always hopes to read a work on Tutuola that contextualises him properly within modern, global literary history. But, perhaps most importantly, one also hopes to be shown a means of discovering how to reread Tutuola; to return him to literature, where he originally belongs; to de-anthropologise him, so that we can experience his jagged poetry afresh.

2. Francis B Nyamnjoh, in Drinking from the Cosmic Gourd: How Amos Tutuola Can Change our Minds, has not adopted such an approach. Instead, he defaults to the paradigm that casts Tutuola as an arrowhead in the perennial struggle between peripheral knowledge and dominant discourse.

Viewed as an exotic, somewhat amusing cultural curiosity by Western readers, and considered an anachronistic embarrassment by the African literary establishment—comprising university-trained critics who were simply scandalised by the manner in which he used the English language—Tutuola has remained in an anomalous position between literature and anthropology, disciplines that have often colluded in discrediting him.

Wittingly or otherwise, because of his apparent lack of verbal sophistication Tutuola from the very beginning made himself the butt of postcolonial anthropology, just as he himself made, albeit with canny mischief, a joke of the English language. Is it possible, now, to free him from this predicament? In several instances, Nyamnjoh, at first, seems to indicate so. He indicts, for example, the standard anthropological treatments applied to Tutuola, reminding us that colonial anthropology with its spectrum of infantilisations is largely inhumane to its colonial subjects—with onward consequences for its place in postcolonial discourse. We constantly need to remind ourselves that the theories of colonial anthropology are foundational ideas in so-called modern civilisation. When we, its erstwhile subjects, peer into the mirror, literally and metaphorically, our image is invariably distorted by their violence. But rather than minimising the impact of Tutuola’s anthropological sequestration, Nyamnjoh prefers to highlight it, thus reaffirming a destiny that might prove to be irreversible for the author.

It should be pointed out that as a social anthropologist Nyamnjoh is quite critical of his discipline’s attitude towards Tutuola, and he is not, in fact, supportive of most of its readings of the author and his work. But by arguing that apparently rustic denizens such as Tutuola ‘are the very same Africans to whom the modern intellectual elite in their ivory towers [try] to deny the right to think and represent their realities in accordance with civilisations and universes they know best,’ Nyamnjoh keeps Tutuola quartered in anthropology’s terrain, where his ill treatment continues, and further prevents his liberation into the freer spaces of art.

Born in 1920 in Abeokuta, Western Nigeria, to cocoa farmers, Tutuola had just six years of formal schooling. His parents were Christians, a background that accounts for the myths, symbols and fables that colour his extravagant fiction. Along with these early influences and themes, there is also the presence of rich Yoruba folklore, filtered through prose that many critics argue is prone to nativist tendencies and thus discordant to the modern African ear. He has, in consequence, been endlessly caricatured by canon builders and literary tastemakers. Nothing illustrates language’s status as a cultural battleground more than Tutuola’s fate: his writing, filled with a kind of Frankensteinian agency that threatens to overpower its arguably inept master, entails that when the moment comes, for Tutuola at least, the consequences are doubly severe.

Had he written in Pidgin, the dialect of postcolonial linguistic subversion and—vitally—reinvention, Tutuola may have been classed as a brave pioneer, as were other far-sighted postcolonial Pidgin experimentalists. Fela Anikulapo Kuti, for one, demonstrated the protean possibilities of the idiom in both song and public discourse. But instead Tutuola tackled a medium—fully-fledged English—that floored him. The rhythms of his language are quite peculiar; in not being a competent user of English, let alone a master of it, Tutola’s own prose frequently prevents full entry into his creative world. His gnarled diction causes the fragmenting of that world in ways that are often unpleasant rather than appealing. In the The Witch-Herbalist of the Remote Town, Tutuola’s offbeat prose is especially rocky:

… it was a great pity that this man could not walk to the altar, because he was totally lame, the hump which was on his back or nape was big as a mound. Again, there was a goitre on his neck which was just like a hillock. So both hump and goitre were a heavy load for him to lift himself up from the ground or floor. Not only that, big boils were all over his body and each was as big as the head of a child. His forehead was deeply dented so much that there was not a person who would like to look at it twice. Not only that, as well his nose was so compact that it was very hard for him to breathe in and out. So for this he had a non-stop hiccups. More, he had one eye only, the other had been totally blinded for a number of years, and his body was also twisted.

Despite the rather gruesome description above, the traditional Yoruba world Tutuola is preoccupied with is generally fluid and filled with luminous beauty. It requires the heightened powers of a poet to convey its startling plenitude, but Tutuola’s jagged and angular syntax—its fundamental disobedience of its master—often produces disastrous results.

Tutuola’s editors at Faber and Faber did him a great disservice in retaining obviously awkward expressions and outright misspellings—for example ‘guord’ instead of ‘gourd’; see also ‘ghostesses’; and so on—in the name of preserving his originality. VS Naipaul—admittedly a man with questionable attitudes toward Africa and her descendents—complained that Tutuola’s English ‘is that of the West African schoolboy, an imperfectly acquired second language’. For his part, Peter du Sautoy of Faber remarked, as quoted by Nyamnjoh:

We do, of course, realise that it [The Palm-Wine Drinkard] is not quite as good as it ought to be, but it is the unsophisticated product of a West African mind and we felt there was nothing to be done about it except leave it alone. When I say unsophisticated, that is not altogether true, since Tutuola has been to some extent influenced by at any rate the externals of Western civilisation.

Despite being ‘unsophisticated’ (it becomes finally impossible to silence the tolling of the bells of colonial anthropology), Tutuola became Nigeria’s first internationally recognised author with the publication of The Palm-Wine Drinkard, which was released by Faber in 1952 and by Grove Press in the United States the following year. Subsequent editions were released in French, German, Italian and Serbo-Croatian. He did not prosper by his fame: Wole Soyinka, among others, was quite vocal in attempting to get foreign publishers to pay the cash-strapped Tutuola his due during his lifetime. When he died in 1997, the fanfare that attended his death surpassed anything he was accorded by his cynical compatriots during his lifetime, but his burial itself was poorly attended, a reflection, perhaps, of the gap that lay between him and the literary establishment all his life.

3. The creator of the imaginative universe that Tutuola’s work is situated in is of course DO Fagunwa, who may be less widely known internationally, but who is by far the more original artist. Fagunwa’s minor global appeal stems from the fact that he wrote exclusively in Yoruba, although some of his books have been translated—by Soyinka, Olu Obafemi and Dapo Adeniyi, among others. It is difficult to imagine anyone else who has done as much to portray the Yoruba cultural cosmos, or succeeded as much in exploring the linguistic richness of the language.

In attempting to celebrate Tutuola, then, we must never forget the incomparable achievement of Fagunwa—who the former sought to emulate, as evidenced by the motifs present in the work of both authors. The exotic cadences of Tutuola’s writing belong largely to Fagunwa, and a revival of Tutuola would be incomplete without a thorough re-evaluation of the earlier Yoruba master, who died in a river mishap in 1963. Fagunwa’s novels, which explore the intersection of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Christianity and indigenous Yoruba spirituality, include Ogboju Ode Ninu Igbo Irunmale, translated by Soyinka in 1968 as Forest of a Thousand Daemons (note the similarity with Tutuola’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts); Irinkerindo Ninu Igbo Elegbeje, translated by Adeniyi as Expedition to the Mount of Thought; and Adiitu Olodumare, rendered in English by Obafemi as The Mysteries of God.

There is very little record of Tutuola explaining himself to the world—liberating himself, as it were, from the gaze and clutches of anthropology; bursting forth in speech and writing regarding his artistic process and existential predicament; stating, if you will: ‘Before you label me, I will name myself, and in this way, I shall indict and contradict you.’ And so Tutuola remains a sort of literary Sarah Baartman; mute, exoticised by the institutions of colonialism and, in death, the uneasy possessor of a hero’s welcome home.

Despite these basic observations informing any critical appreciation of Tutuola, Nyamnjoh’s main strategy is to stress the complementary relationship between literature and anthropology, and to emphasise why the latter ought to seek interconnections with the former in order to bolster common understandings of social texts. Nyamnjoh makes a strong case for this collaboration’s ability to rehabilitate figures such as Tutuola. However, I would argue, in spite of all the obvious difficulties, for Tutuola’s complete adoption by literature.

There will always be a high degree of uncertainty around the manner in which Tutuola will be critically considered: nagging doubts about him being no more than a naive primitivist; misgivings about the worthiness of the literary sub-genre his writing gestures toward (call it ‘African magical beat’, if you will); and befuddlement concerning the cultural loss and confusing hybrids that are the result of the colonial encounter, both in Nigerian reality and in Tutuola’s mind. Fractured prisms, cracked mirrors—it is most probably through these purveyors of ‘what might have been’ that Tutuola is forever condemned to be judged.

And yet there is a further context in which Tutuola’s art would make absolute sense: that supplied by Yoruba culture, with its lush pantheon of deities, cascading myths, self-perpetuating folklore and legends. Here, I believe, is where a viable literary approach to Tutuola’s work lies—one in which he continues in the footsteps of his illustrious artistic forebears, Fagunwa et al., as both innovator and custodian of tradition.

For if Fagunwa adopted Christianity and sought to proselytise it virtues, it was not done at the expense of concealing his dense precolonial Yoruba heritage. Indeed, instead of projecting Christian modernity, we are assailed in his works by an overwhelming sense of interwoven pre-Christian entities. It is clear that Tutuola was deeply inspired by that partially-occluded world and sought to reimagine it with varying degrees of success.

As for Soyinka, his adoption of Ogun, the Yoruba deity of metallurgy, war and the lyric arts, remains the essential foundation of his own art. In the same vein, visual artists such as the Nigerian sculptor Twins Seven Seven and the Argentinian-born Bahian artist Carybé both celebrate ancient Yoruba cosmology and divinities in a manner in which their distinctiveness and power are inherently unquestioned. It is possible to give Tutuola a similar critical reception—that is, as a noteworthy explorer of the Yoruba cosmological universe. One hopes that one day this will be the norm, rather than the exception.

So perhaps the joke is on us, who seek after all to apply the standards and conventions of both ‘Western’ and ‘world’ literature to Tutuola’s work. Perhaps, more than Tutuola himself, we are in need of intellectual decolonisation, if we are not able to read his work as a probing subversion of the colonial mindset.

Tutuola’s life and work evoke a vexing question: how can one be so vividly anti-literature and so dedicatedly pro-writing at the same time? You can be, if you are a historical misfit caught on the cusp of tumultuous colonial transformations, and able to create stories through a splintered, prefabricated, partially-undomesticated idiom, one that has shrugged off various foreign and domestic superstructures, and is wholly your own.