Shiraz Durrani and Kimani Waweru

Vita Books, Kenya

Vita Books was established in London, UK in 1986 to “publish progressive books on issues related with anti-imperialist struggles and with the establishment of just and democratic societies”. This remains its vision today. Over the years, Vita Books has worked with many progressive individuals and organisations. For a time, it published books in partnership with the Mau Mau Research Centre, then based in New York, now in Kenya. It was always the intention at the time of its establishment that Vita Books be based in Kenya which has provided it with its main inspiration.

December 2017

Stephanie Kitchen (SK): Vita Books was established as a

progressive/radical publisher just over 30 years ago, moving from London to Kenya in 2016. What do you regard as your most notable

achievements to date?

Shiraz Durrani (SD) and Kimani Waweru (KW): In most publishing companies, profits are the ultimate aim. Vita Books was not set up to make

money, but as an aspect of the political activism of its founders. These activists shared the vision of the Kenyan underground December

Twelve Movement (DTM) which later emerged as Mwakenya-DTM. However, Vita Books was not part of any political movement and remains an

independent entity.

Vita Books was established in 1986 by Kenyan activists who took refuge in Britain from Daniel arap Moi’s dictatorship. At one level, it was designed to disseminate information relevant to working people and their anti-imperialist struggle in Kenya. The Kenyan ruling elite had continued to promote the colonial perspective of people’s resistance to colonialism and imperialism, and that became the official version in education, mass media and national consciousness. Those involved in establishing Vita Books saw an urgent need to tell an alternative version of the history of Kenya and people’s resistance to imperialism. A new mindset had to be created to show the reality of the oppression and exploitation that had impoverished the majority of the country’s people.

At another, more immediate level, the push to establish Vita Books came from the need to publish a book written in Kenya in the early 1980s: Never Be Silent: Publishing and Imperialism in Kenya, 1884-1963. Its content made it unlikely that a local publisher would be able to print it. There had been discussions with a local bookshop, Heritage Books, to publish it in partnership with Vikas Publishing in India. However this attempt came to an abrupt end when the author had to flee Kenya for London in 1984. Approaches made to various publishers in UK indicated that there was no interest in publishing the title, as the subject matter was too specific to Kenya and there was no market for such material. From that point, it was easy to take the next step and set up Vita Books to publish material that had no market in UK and could not be published in Kenya for political reasons. Thus, politics and publishing came together to establish Vita Books. This is also reflected in the name of the company. Our last publication, Liberating Minds, explains the name, Vita Books:

The term vita in Vita Books needs some clarification, as too often it is seen in the West as derived from the Latin for ‘life’. As used here, however, vitais taken from Kiswahili, the national language of Kenya, in which it translates as ‘mapigano baina ya makundi, watu, wanyama, mataifa’.[i] In the Standard Swahili-English Dictionary,[ii] vita is defined as‘war, battle, fighting, contest, struggle’. We used it here to indicate a struggle for relevant information. In addition, the term vita also relates to vitabu — Kiswahili for ‘books’. And the dual aspects of its name — struggle and books — are captured in the Vita Books’ logo.

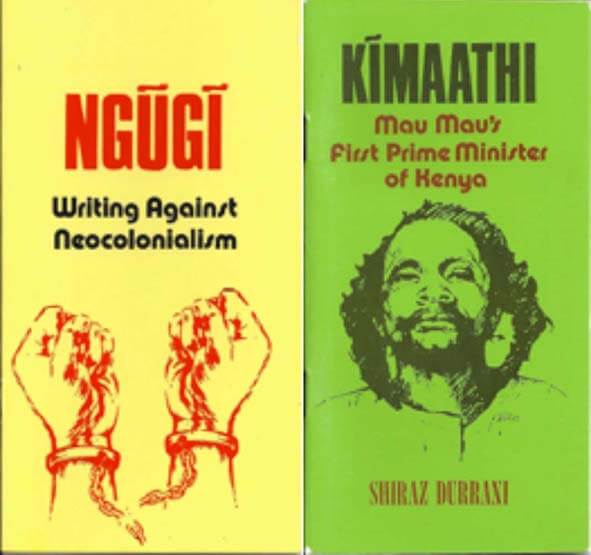

Vita Books started with two booklets in 1986: Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Writing Against Neo-colonialism and Shiraz Durrani’s Kimaathi: Mau Mau’s First Prime Minister of Kenya. These set the tone of the publisher and proclaimed its anti-imperialist outlook. It also challenged the prevailing interpretation of the history of Kenya, Mau Mau and Dedan Kimathi, its leader.

First two publications

And so to your question. Given the above background, perhaps the most important achievement has been that Vita Books has managed to survive

all these years and maintained independence from corporate interests. It has continued to publish material meeting its aim of making

progressive, alternative ideas and experiences available to working people. Vita Books works on the basis of self-reliance and does not aim

to join the ‘big’ players in the publishing world. This has enabled it to maintain its anti-imperialist outlook. This is particularly

relevant today when for example powerful corporations such as Taylor and Francis can force important journals such as the Third World

Quarterly through

publication of an offensive (and latterly retracted) article ‘The Case for Colonialism’ to abandon the ‘values of the journal’ which at one

time stood ‘above the fray when neoliberal ideas swept through the academies of the world, demanding that public sector development be given

over to private sector’ (Prashad 2017).

Had Vita Books depended on external sources of funding, it would have had little chance of maintaining its policy of publishing ‘progressive books on issues related to anti-imperialist struggles and with the establishment of just and democratic societies’.

But this independence has come at a cost as there are no large funds to publish material that we would like to publish. Lack of funding

affects not only the cost of production of books, but also staffing. Vita Books has no full time staff and relies entirely on time and

resources of some founder members and many others who are committed to its vision. But we value our independence and are more interested in

ensuring the quality of what we publish, not the number of titles we bring out. This has enabled us to maintain a high profile and presence

in politics as well as in publishing.

Surviving for so many years would be one achievement, but there is also the need to ensure our future. Long-term sustainability and generational shifts are equally important. This was achieved when Vita Books moved to Kenya in 2017 – a landmark move for the company. The move to Kenya roots Vita Books within working class struggles in Kenya. While this may have adverse political implications in terms of its long-term survival and independence, not to mention the risk to those involved in its work, it is a necessary step to go back to its roots, as otherwise it would remain an external entity divorced from its true audience, subject-matter and roots.

In short, the ideas and ideals that gave birth to Vita Books are constantly renewed as the organisation is re-energised by the various political and social projects it has initiated or come to be associated with, some of which are mentioned below.

The appointment of African Books Collective is likely to provide yet another advantage for the future. Its use of Print On Demand technology reduces the need for large print runs and financial outlays, so it is possible to extend our publishing programme. Vita Books now prints copies only for the Kenyan market where it is considered important to carry paper copies.

SK: Could you say something more about the areas you publish in? From your website and booklists, I get a sense of (liberation)

history and (left) politics, but also translations of key historical/literary texts and books in Swahili?

SD and KW: The subject areas we publish in are influenced very much by the political and information needs of working people in Kenya. As a neo-colony, Kenya has continued the imperialist-imposed practice of ‘TINA’ (There Is No Alternative – to capitalism and imperialism). This has affected political as well as information struggles in Kenya, as it has in other countries in a similar situation. That is why Vita Books focuses on areas that are obvious ‘vacuum areas’ created by the ruling elites. One such area is socialism as an alternative to capitalism. In this sense Vita Books has unashamedly taken sides with the struggles of working people and seeks to expose the oppression and exploitation inherent in the current political and economic set-up.

That forms the content of what Vita Books publishes. But the form of its publications also reflects the needs of the intended audience. One aspect of this is the language of publications – as imperialism seeks to downplay information and culture in minority languages, focusing on English. Thus our last publication was a dual-language one, with articles in Gujarati and English. One of our forthcoming books – Tunakataa! –is a dual Kiswahili-English collection of resistance poems. This language policy also enables us to reach a readership we would not reach if we published in English only.

In a multi-lingual, multi-nationality country such as Kenya, Vita Books also recognises the importance of the availability of different types of resources. We are interested not only in historical topics, but also in arts, culture and literature. One of our future books is a collection of poems and future plans include a collection of short stories by young people struggling for survival in a hostile and unequal society.

Format is also important to Vita Books. The first two booklets published in 1986 (by Ngugi and Durrani) were small format easy to read booklets which could be carried around and hidden from special branch officials on the lookout for ‘subversive’ material.

In keeping with its aim of making alternative ideas and experiences available, Vita Book set up the Notes and Quotes Series which are

presentation slides on specific themes that are easy to read and follow. They are available, with other material, for free download on the

Vita Books website.

Vita Books plans in the near future to address another important gap in the information field in Kenya. Many important books on the history

and politics of Kenya are now out of print partly as a result of the government’s decision not to include them in school curricula and

partly as publishers close down or find it uneconomical to keep such books in print. Vita Books is planning to reprint an important set of

such books in 2018. A difficulty in reprinting such material concerns copyright. Publishers need resources to get legal advice on their

ability to reprint out of print material.

SK: Could you say something about the networks of authors and activists you have established, in Kenya, London, the US? How do

they help support and promote your publishing programme?

SD and KW: Vita Books does not have a network of activists or authors in the traditional sense. It operates on a different level altogether.

It is the political aspects of its work that connects it to the struggles of people in Kenya and elsewhere. In this sense its work is based

on ‘politics first’ and its publishing activities are aspects of, and reflect, its political outlook and connections.

Over the years, Vita Books has worked with other organisations in the publishing and book fields. These include New Beacon Books in the UK, briefly Africa Word Press (US) and the Mau Mau Research Centre, then based in US. Vita Books co-published the Gujarati articles from its recent book, Liberating Minds with the Gujarati online journal, Opinion.

As an activist publisher, Vita Books gains contacts, strength, ideas and experiences by being involved in a number of joint projects, which it has either initiated or been involved in. For example, it has been involved in, and learnt from, the Three Continents Liberation Collection at C.L.R. James Library in Hackney in the 1989. Other projects include Diversity, Skills for a Globalised World, the Quality Leaders Project and the Quality Leaders Project (Youth), and the Progressive African Librarian and Information Activists’ Group (PALIAct).[iii] PALIAct has just been revived in Nairobi. Vita Books is helping to establish the PALIAct Liberation Library in partnership with PALIAct and Mau Mau Research Centre in Nairobi.[iv]

Besides its links with progressive political movements, Vita Books’ involvement in such projects provides it with a network of progressive organisations and individuals. In keeping with the development of information and communications technologies, the Vita Books website provides additional material such as documents, articles and books which are available for free download as part of its policy of making relevant material available in a form and place that meet users’ needs.

All this indicates that Vita Books is not a traditional publisher but an activist organisation involved in progressive information, communication and publishing activities in the interest, not of profit, but of a free flow of relevant, alternative information for social and political transformation in the ‘neo-colonised’ world.

SK: What is your impression of general non-fiction publishing in Kenya, i.e. publishing that is distinct from school textbooks publishing/popular novels etc? Who are the other players? What are the major challenges?

SD and KW: In Kenya, reading is not encouraged as part of the culture. There is a mindset among the population that reading stops when one finishes school. This impacts greatly on the sales and publishing of books, particularly non-fiction, and most bookshops shy away from stocking such books as not many people buy them.

This culture has not been challenged by relevant institutions, and promoting a reading culture, for fiction as well as non-fiction, is not a priority. A small attempt to address the issue has been made this year (2017) by the Progressive African Library and Information Activists’ Group’s (PALIAct) set up the PALIAct Liberation Library, in partnership with Vita Books and the Mau Mau Research Centre. The initiative intends to promote and encourage reading, study and research. Although its stock at present consists of mainly non-fiction, fiction is very much part of its future plans.

Another area that needs attention is alternative magazine publications. Magazines have the potential to reach all age groups and can be fiction or non-fiction. Traditional magazines do exist but are mostly aimed at middle class readers. The need is to develop new magazines in terms of content as well as in language and forms that are relevant to working people. The democratic space in Kenya has widened a little, at least for the time being, as compared to some years back, and this has made it possible for current magazines and daily newspapers to report news that in the past was viewed seditious by the regime. This means that the reportage of progressive news has improved even if the magazines and newspapers are owned by the ruling class. And yet, it is hard to get progressive magazines in Kenya – the few that report politics are controlled by the middle classes and reflect their reality, taste and needs. The need is for working people to own and control magazines and book publishing so as to reflect the world from their point of view. Development in new technology may provide one way out for them.

Urban youth have their own language, culture and lifestyles. Empowering them to develop magazines can have a dramatic impact on national reading, learning and entertainment.

An important factor in book publishing is the content of books published. Most are aimed at an affluent, relatively well-off people with spending power. Yet there is an unsatisfied need to reflect lives of working people, which remains only partially fulfilled. Addressing this issue can increase demand and boost the publishing industry and people’s reading at the same time.

Public libraries can also play a more active role in encouraging reading and writing of fiction, but are limited by government policies.

SK: This brings me to the question of audience/readership for your books. Do you have a sense of where your books are read and used? Do you publish eBooks as well as printed books? How do you promote your books – in Kenya, regionally in East Africa and internationally? Do you know which libraries stock your books?

SD and KW: Where we sell our own books directly, we of course are aware of who the buyers are and from which countries. This includes a number of countries in Africa, Europe, the US, Canada and Japan. Bookshops from some of these countries have requested copies, either for sale or to stock. In Kenya, a number of local bookshops such as Prestige, Bookfast, and the Bookstop at Yaya Centre stock Vita Books.

However, it was difficult to know who the buyers and their countries are when we used distributors such as Global Books Marketing in the UK and Africa World Press in the US. We hope to get more detailed sales reports from African Books Collective who started marketing our books from 2016.

At the same time, in keeping with our attempts to make relevant material available to those who need it, particularly in Africa, Vita Books has donated a number of titles to various public libraries in Africa through a partnership with Book Aid International. They gave feedback on one of the titles,Progressive Librarianship:

I thought you may like to know that we have had some feedback from Kenya National Library Service about your book, Progressive Librarianship. In the annual partner report for 2014 they specified that they would like to receive more copies of this title! We have now distributed all the copies you kindly donated to us ... your book was appreciated by librarians in Kenya.

‘Your book [is] on the shelf of Zimbabwe Open University, Bindura! They have a copy in each of their 10 library branches’. (Email from Book

Aid International, 23 September 2015)

Another way of assessing the usage of Vita Books is to look at academia.eduwhere some books and other information on Vita Books publications are available for free download. A brief analysis from the site shows the following:[v]

1. Mau Mau the Revolutionary Force from Kenya (2012, an earlier conference presentation of the forthcoming book, Kenya’s War of Independence) was viewed 1,348 times and downloaded 63 times.[vi]

2. Kimathi, Mau Mau’s First Prime Minister of Kenya (1984) has been viewed 341 times and downloaded 46 times.

3. Never Be Silent: Publishing and Imperialism in Kenya (2006) was viewed 235 times and downloaded 27 times.

4. Makhan Singh, A Revolutionary Kenyan Trade Unionist was viewed 451 times and downloaded 26 times; in addition earlier presentations on which the book was based was viewed 52 times and downloaded 55 times.

As far as distribution by countries is concerned, the analysis shows the views as coming from the following countries:

• Kenya: 829 views

• USA: 800

• UK: 660

• Unknown: 5,992

• Africa: South Africa: 45; Nigeria: 43; Zimbabwe: 41; Uganda: 37; Tanzania: 27; Namibia: 9; Zambia: 8; Algeria: 7; Botswana, Côte d’Ivoire: 6 each; Mauritius: 5; Ethiopia: 4; Egypt: 3; Ghana, Lesotho, Senegal, Sudan: 2 each; Morocco, Mozambique, Senegal: 1 each.[vii]

• Other countries: India: 161; Canada: 123; Australia: 43: Indonesia 34; France: 29; Germany 28; Pakistan: 25; Argentina: 23; Philippines: 22; Portugal: 20; Brazil: 18; Mexico, Netherlands, Spain, Turkey: 17 each; Norway: 15; Ireland: 14; Iran: 11; Denmark: 12; Greece: 12; New Caledonia: 12; Saudi Arabia: 10.

• Other countries with 10 or less include: Malaysia; Peru; Romania; Russia; Taiwan; Ukraine; Venezuela; Vietnam.

• A total of 94 countries are listed in the Views.

The chart for the year 2016–17 shows the continuing popularity of the 2006 publication Never Be Silent.

Durrani, Shiraz, 2006, Never be Silent: publishing & imperialism in Kenya, 1884-1963, Vita Books. Source: http://eprints.rclis.org/8127/, [Accessed 7 October 2017].

These figures indicate that there is a huge demand worldwide for progressive material, such as those published by Vita Books. Such usage, of course, is not reflected in print sales, perhaps indicating the need for exploring innovative ways of making such material available cheaply, in non-print formats as well as the use of the internet as a distribution network. Such work is obviously beyond the scope of Vita Books on its own but the implications for publishers, booksellers and distributors are clear. One can only speculate what the impact of Vita Books would have been if it had more resources to promote progressive material.

As for your other questions, Vita Books publications are now available in e-format as well. Marketing and promotion is undertaken through a

number of ways: presentations at conferences, book launches, word of mouth, reviews in newspapers and magazines, through the Vita Books’

website as well as mailing publicity material on social fora and through individual mailing lists to progressive lists and individuals. Vita

Books also produces publicity material for use at conferences and meetings. These include the Vita Books canvas, bookmarks with cover images

of its publications, key chains etc.

Publicity in Kenya is an interesting case. When the first books were published in 1986, they were circulated underground as the political

climate made it inappropriate for open sale and distribution. Some bookshops at that time for instance kept the book, Kimaathi: Mau

Mau’s First Prime Minister of Kenya,

under the counter and sold only to trusted customers who got information about the book through progressive political links. A sad episode

related to this book was the death of Karimi Nduthu, ‘a Mwakenya activist, a political prisoner, a human rights advocate’ who was ‘brutally

assassinated by agents of the Moi dictatorship’ on 23 June 1996. According to a report by the Release Political Prisoners pressure group, at

the time of his assassination, ‘Police arrived on the scene within minutes…. They then carried Karimi’s body, his tape recorder, typewriter,

cassettes, books, papers and other documents’. Among these were many copies of the Vita Books’ publication, Kimaathi, Mau Mau’s First

Prime Minister of Kenya which

he used as study material for those he was in contact with. Subsequently, Vita Books and the Mau Mau Research Centre published the book, Karimi

Nduthu, A Life in the Struggle as

‘a celebration of the immortality of the selfless dedication of a truly remarkable person’.[viii]

Publicity in Kenya is an interesting case. When the first books were published in 1986, they were circulated underground as the political

climate made it inappropriate for open sale and distribution. Some bookshops at that time for instance kept the book, Kimaathi: Mau

Mau’s First Prime Minister of Kenya,

under the counter and sold only to trusted customers who got information about the book through progressive political links. A sad episode

related to this book was the death of Karimi Nduthu, ‘a Mwakenya activist, a political prisoner, a human rights advocate’ who was ‘brutally

assassinated by agents of the Moi dictatorship’ on 23 June 1996. According to a report by the Release Political Prisoners pressure group, at

the time of his assassination, ‘Police arrived on the scene within minutes…. They then carried Karimi’s body, his tape recorder, typewriter,

cassettes, books, papers and other documents’. Among these were many copies of the Vita Books’ publication, Kimaathi, Mau Mau’s First

Prime Minister of Kenya which

he used as study material for those he was in contact with. Subsequently, Vita Books and the Mau Mau Research Centre published the book, Karimi

Nduthu, A Life in the Struggle as

‘a celebration of the immortality of the selfless dedication of a truly remarkable person’.[viii]

Examples of publicity

Vita Books gets publicity by participating in events and their authors giving talks at conferences and meetings. Two examples, given below, are based on books later published by Vita Books:

Available at: https://soundcloud.com/pop-samiti/shiraz-durrani-speaking-at-the-kenya-land-freedom-depository, accessed 6 November 2017.

SK: You have also published a major monograph titled Progressive

Librarianship,

What could ‘progressive librarianship’ look like in Kenya and other African countries today?

SD and KW: The prospects of developing progressive librarianship (PL) in Kenya – and Africa in general – are essentially linked to people’s struggles for liberation. As the political, social and economic situations in a country change, so does PL. PL is not a static concept applicable in all countries and all situations. It is thus important to see the conditions in Kenya and Africa now before one can decide what PL should look like.

The need for PL arises from a total grip over people’s lives and resources by capitalism and imperialism. That PL has not emerged to a significant level, as it has in, say, the US and some European countries is not due to a lack of initiatives or ideas. It is the political and economic situation that has strangulated progressive initiatives in every field in Kenya. The ruling classes, with active support from imperialist countries, ensure that no avenues are open to progressive ideas and actions. Thus the first requirement for any PL movement is to liberate people’s minds from an imperialism-induced mindset informed by few alternative ideas or experiences, from Kenya or the world. John Carlos’s assessment, quoted by Gary Younge (2017), that ‘It’s not the responsibility of the oppressor to educate us. We have to educate ourselves and our own’ is relevant for all those involved in professional librarianship.

It is not in the interest of those who benefit from the spoils of capitalism and imperialism to educate those they exploit and oppress about their history of resistance or about the reasons for their poverty. Thus libraries and publishing firms entrenched within the laws and regulations of the capitalist state are, by definition, not capable of breaking out of the mould set by the ruling classes.

As far as Kenya is concerned, it is essential to understand the reasons for the situation in which working people find themselves today. It is on that ground alone that PL can chart out its policies and programmes. Yash Tandon (2017) highlights the situation in Kenya:

My understanding is that independence is an important achievement, but it manifests itself only at the political level and that, too, only partially. The economy is still not liberated from the control of the empire, and so even its politics are compromised. I would state unhesitatingly that Kenya is a neocolonial state. There is convincing evidence that the economy is still largely in the hands of imperial finance capital, even if there are pockets of ‘national’ capital in the little market left to the indigenous people.

Tandon (2017) highlights an issue which should be at the forefront of PL:

Through experience, we leant that the fundamental problem is not the class character of our petty bourgeois leadership (although that is a strong contributing factor), but the system of imperial domination and the neoliberal ideology that imprisons our mindset (including some of the best economists in our universities), and those in the state who make policies in the name of the people.

This reality points to the need for a different model of PL in Kenya and Africa from that in the US or Europe. The PL movement in Kenya needs to pay attention to some of the key issues raised by Tandon as well take advantage of some developments in technology and social trends. However, with all the difficulties, there are indications of progressive activities in the information, library and cultural fields, indicating that there is hope for radical change which often starts with small steps.

Developments in technology have provided new communication tools, storing and disseminating relevant information fast and enabled specific communities in to be reached in appropriate languages. Examples are the ‘Kenya Information Liberation’ group, the ‘Kenya Palestine Solidarity Movement’ and the ‘Dunia Yetu (Our World)’ on the Telegram messaging service. The latter aims to ‘Highlighting news of popular resistance against arrogant powers & news you won't see in the mainstream or local media, with a focus on MENA [Middle East, North Africa] & Eastern Africa regions’.

Besides Kenya-wide groups, there are important African networks that circulate alternative, progressive ideas and views. An example is Pambazuka News which is an important alternative voice on the continent. At an international level, besides Whats App and Telegram, Facebook and Twitter have become a way of life in Kenya where mobile phone availability has spread at a rapid rate. Examples of a critical service is the ‘Crimes of Britain’ site on Twitter which carries brief reports from history that can help to increase awareness of the reality of the history of Kenya and Africa.

An example of an important internet-based resource for a study of African history is the South Africa-based South African History Online (SAHO) whose mission is ‘to promote the study and teaching of history and to make knowledge accessible through the creation of a comprehensive online encyclopaedia of South African and African history. Furthermore, through developing partnerships with community-based history projects, museums, archives and educational institutions it provides a platform for people to tell their stories’.

Today, PL needs to work with progressive publishers, booksellers and cultural activists. While there are not many examples of the former two in Kenya, the latter is an expanding field. An example is the group Mau Mau Arts as expressed in their short video ‘Art is the Weapon’ and whose work in all areas of creative activity is impressive in addressing people’s needs via artistic expression. It is interesting to note their interest in issues around literacy and learning and initiative in building a library.

There have been significant changes in the world in the last 10 years or so, not only in information and communications technologies, but in global economic and political forces. The rise of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) group has created a new geo-political situation with the power of US and its Western allies in comparative decline. China’s presence in industries, trade and other fields in Africa has also altered the African situation where the Western capitalist model was the only one available in the past.

In this changing situation, progressive politics and librarianship also need to change. Ideas that were relevant even 5 years ago need to be re-examined and amended. In addition, practices in other continents (the US, Europe) cannot be used without adaptation in Africa. This calls for serious study and the creation of a new body of ideas and practices that are relevant to a neo-colonial situation.

Learning from the past

Coming back to your question about what PL could look like in Kenya today, there are two points to be mentioned at the outset. First of all, any ideas for any social system or institutions cannot be examined in isolation from the actual political and economic situation on the ground and from the perspective of the needs of working people who form the majority of the country’s population. Secondly, it is not ‘experts’ who sit in offices in Nairobi or London or Washington who will provide solutions to social problems. It is the people themselves who will find their solutions based on their own experiences and understanding of realities around them and their experiences. Those interested in developing any progressive and alternative projects or systems would do well to keep these two points in mind.

The reality that Kenya faces under capitalism and imperialism is that people lack power to make their own changes and they lack the voice to raise their concerns. The first task of PL has to be to create conditions to enable those whose voice has not been heard to be heard. Similarly they need to create conditions to enable those without power to gain effective power in the information field by getting access to progressive, alternative news, views and experiences from Kenya, Africa and the world. Note that we are not saying that progressive librarians become the voice of the voiceless or that they give power to the powerless. Their task is to help create conditions where people can raise their own voice and can take their own power. It is in this sense that ‘the professional is political’ as Durrani and Smallwood (2006) say. They also mention the need to understand neutrality in libraries, under which much inaction is justified:

Thus the myth of the ‘neutral’ librarian needs to be exploded. There is no way that librarians are or can be neutral in the social struggles of their societies. Every decision they make – how much to spend on books, which books to buy, what staff to appoint, how to manage the service – is a reflection of their class position and their world outlook.

Progressive librarians will need to explore creative alternatives. It is only on that basis that PL can make an impact. There are other issues that PL will need to address. One of them is to challenge, in practice, individualism instilled among people by capitalism. There can be no progress unless a cooperative, not a competitive, approach in information work is adopted. They will need to learn from people and in turn help people develop their ideas on through practice. They would then help people turn their ideas into action.

A project-based approach is more appropriate in developing new services and in giving staff new skills and experience in the practice of developing these new services. But we are not starting with a blank sheet of paper. A large body of practices, theories, ideas and experiences have been devoted to showing that a new approach using pilot projects is not only possible in theory but in practice too. So we respond to your question of what PL could look like by recalling some experiences where practices associated with PL have been developed in Kenya.

Fuller details of most of these projects have already been published, so there are only summaries here, with references to the source for those interested. An overview of the success or otherwise of this project-based approach is given at the end of this section.

Progressive projects for change in Kenya:

School and College Library Project, Kenya

School and College Library Project (1983-84), which provided relevant articles on history, geography, and culture, all from local research, to a large number of schools and colleges throughout the country. Part of the material sent was a package on organising a small library with instructions on simple cataloguing and classification, processing, borrowing systems, author and subject catalogues, and other basic practices. This was extremely popular with schools that had also started contributing their own documents in the system.[ix]

Sauti ya Wakutubi – Voice of Librarians

It is in this context that one sees the significance of publications such as Sauti ya Wakutubi (1984) from the University of Nairobi library services. Short-lived as it was, with just four issues, it has made a lasting impression on the library scene not only in Kenya but in other parts of the world which have similar conditions. Its chief contribution was that it gave an outlet to the silent majority of library workers whose professional views have never before been considered worthy of publication or implementation. The significance of these views lies in the fact that they address local conditions and give local solutions in a situation where alien methods have too often held sway in the past. Their main contribution is that they unashamedly take sides in supporting the needs of the working people and do not disguise the need for change in the library and information field. The workshops organised by Sauti ya Wakutubi sum up the lessons on information work:

‘the need to reorient librarianship in Kenya to the requirements of the majority of Kenyans was emphasised.... Most of our libraries at present are copies from the Western libraries. We do not have libraries that suit our context at the moment. The mistake so far made in our library system is that we have confined and concentrated ourselves to small communities who are learned or rich, instead of extending our ideas to rural communities’.[x]

Sehemu za Utungaji – The Creative Wing

The Sehemu ya Utungaji started initially as the creative wing of Sauti ya Wakutubi, to provide artwork for the magazine. Gradually, its scope expanded and it began experimenting with various ways of providing a relevant information service. One such was the School and College Library Project. Another project of the Sehemu was to make the film medium available to the people. Thus film shows were organised where many who had not in the past been exposed to films were attracted particularly because the content was relevant to the lives of the people. Similarly Sehemu also joined hands with a city theatre group and produced a play with a historical theme. This also attracted a wide audience and much media coverage nationally, including in the Kiswahili press. Such shows gave people a pride in their own indigenous history.

Yet another project involved producing a pictorial interpretation of Kenya's history entitled Kuvunja Minyororo ('Breaking the Chains'). This project encouraged members to draw pictures, undertake historical research and work out ways of interpreting this history for a larger audience.

These and other projects pointed the way to how a library service should make use of its resources (humans, books and materials) in order to provide a communication link with the people in their own language and in an appropriate form. Here also the crucial point was the content of such communication.

Scene from the play, Kinjikitile, Maji Maji (1984) performed and produced by Sehemu ya Utungi and Takhto Arts. Directed by Naila Durrani, member of December Twelve Movement and Takhto Arts

The Library Cell’s Work

While the underground press of the December Twelve Movement (DTM) was used by the Library Cell to disseminate information and create wider awareness of issues facing the society, it did not ignore the open, democratic, public spaces that were still available in the restrictive environment. New democratic avenues were opened up as old ones were closed by government action. Drama was one such avenue, the running of Library Workshops another, and the setting up of journals and magazines yet another. Many articles were written for workshops whose proceedings and discussions were published in journals and the press. Some were published in international journals to gain wider exposure and legitimacy for the views expressed.

At the open, democratic level, the Library Cell involved itself in writing and publishing books and journals and also in producing plays with relevant themes. It soon began to influence a large number of library workers across the capital and to expand to other towns. Wider support among librarians and academicians for the work of the Library Cell is indicated by the large number of library workers who sought to make the Kenya Library Association move towards a progressive position by the large number of people who attended its workshops from all across the City and by the large mailing list of the University of Nairobi Library Magazine.[xi]

PALIAct: The Progressive African Library & Information Activist’s Group

The situation of public libraries in Kenya and many African countries falls short of meeting the needs of all. There it is compounded by the lack of national resources allocated to libraries, a lack of creativity and unwillingness to challenge the status quo among senior professionals. Thus the situation has remained the same since independence in the 1960s in most countries of East Africa, with possibly some improvement in the quantity of the service, but no major change in the quality and direction of the service. It was a conservative model from Britain that remains the dominant one in Africa as well, at least in the English-speaking parts.

Progressive librarians sought to provide a model for librarians in Africa in an attempt to develop an alternative system. They based their proposals on experiences in Kenya as well as some positive experiences from other initiatives. Public libraries in most of the countries in Africa are as difficult to change as those in England. The proposal developed by progressive librarians was to empower middle and lower-level library staff to work with local communities and bring about change from below, without having to challenge the present power-holders if they are not positive towards moving in a new direction. The proposal was a progressive agenda entitled the Progressive African Librarian and Information Activists’ Group (PALIAct). This was an initiative based at the Department of Applied Social Sciences (DASS) at the London Metropolitan University. It was a partnership with a group of progressive African librarians and information workers. PALIAct sought to develop people-oriented information services decided upon by workers, peasants, pastoralists, fisher people and other marginalised individuals and groups whose information needs had not been met. It involved working in partnership with other professionals and service providers. PALIAct operated on the principles of equality, democracy and social justice and encouraged a pan-African world outlook among information and community activists. PALIAct saw relevant information as a basic human right.

PALIAct provided a vision for a people-orientated information service that could meet the information needs of workers and peasants. It worked towards providing an anti-imperialist and pan-African outlook among African librarians and information workers. It also sought to set up an alternative information service in partnership with the potential users of the service as a way of showing what needed to be done. PALIAct aimed to form partnerships with progressive librarians and information and other workers within Africa and overseas.

An important principle that guided PALIAct was that there should be a strong partnership between information professionals, communities and groups. This was to ensure that librarians did not work in isolation as happens in the conservative service. At the same time, it was considered important that whatever new services were developed should reflect the real needs of communities as decided by the communities themselves. For this to happen, it was essential that communities were active partners and decision-makers in planning and monitoring services.

As the name of the organisation suggests, PALIAct was made up of activists, not those who talk but take no action. Active participation was essential if real change was to be achieved. PALIAct recognised that the struggle for a relevant information service was intimately linked with the political struggles of the people to ensure that material, social, cultural and political needs of the people were met.[xiii]

Within their own space, all these and others not mentioned here were mostly successful in developing and implementing new services and also increasing learning and skills of staff, thus making the services sustainable when there was a will to do so. One can think of the projects as ‘innovation sparks’ that traditional, conservative librarianship is not able to develop and only a progressive approach can do. Some of the key elements of this approach are considered below.

All the projects were developed in close partnership with the intended communities whose needs were first assessed. They looked at aspects of a successful development of services, the service itself and the training of staff. Learning opportunities and opportunities for gaining experience in developing leadership qualities were integral to the projects. In some cases, opportunities for staff development ensured that the innovative project approach was mainstreamed and did not remain as a bolted-on, marginalised service. Under the Quality Leaders Project, academic credits and certificates were added for staff as the training was planned and delivered by London Metropolitan University.

And yet, none of the projects survive today. This was in the very nature of the projects: they were added on to a conservative establishment. With all the attempts to ensure long-term sustainability, the conservative establishment did not allow this challenge to the status quo to last long. It took the first opportunity to get back to the traditional approach. Whereas staff who were active in the projects were keen to continue with them, the conservative leaders who held power opposed change. This points to the lack of power in the hands of lower level staff and communities to demand services they needed and were keen to develop. Their needs and wishes could easily be ignored once the conditions that gave rise to the initiation of the projects changed – in some cases when key people behind the projects left or a new senior or political leadership deemed these innovative activities as unsuitable. So in the end it was a power struggle between the old and the new, between meeting the needs of the middle classes and those of working people.

The question then arises: were there any benefits from these projects? There certainly were. While they lasted, they met the needs of communities as well as ensuring the staff involved got training and job satisfaction in developing and delivering a relevant service. That the projects did not survive over the long term does not take away their positive contribution while they lasted. At the same time, they all created a large body of ideas and experiences – almost all well documented – which enriched literature on PL, community development, staff training and other fields, including the development of teaching and learning curricula at university-level. Most such material is available at the Vita Books website under ‘Projects For Change’.

Communities and staff who were involved in these projects recall and desire such practice even to this day, as evidenced by responses and reactions received in various ways. Such experiences then become part of communities’ wisdom as they realised that there are alternative approaches to meeting people’s needs. Such experiences also expose the ‘professional’ bodies and institutions which remained largely outside the projects, sometimes dipping their toes in just to be able to claim they are part of the progressive movement and support communities in their desire for new services.

In view of all this, a legitimate question is whether there is any prospect in Kenya for a PL approach. At the level of the professional bodies and institutions, there is very little chance of them taking on board the alternative progressive approach. As far as the government is concerned, there is a currently a reluctant tolerance of such activities, but no great enthusiasm. Both these are understandable as both are deeply rooted in, and reflect, the values inculcated by capitalist relations which is the official policy of the country.

And yet that is not the end of PL in Kenya. The unofficial sector is thriving in Kenya – in industries, employment, arts and many other fields – all without official support or encouragement. The information field is similar. Some of the earlier projects in the 1980s, such as Sehemu ya Utungaji, as well as the establishment of PALIAct in Nairobi in 2006, survived among some workers and community members.

An indication that PL is taking roots in Kenya is two developments taking off in the last year or so. They are linked with the revival of the Progressive African Librarian and Information Activists’ Group (PALIAct) in 2017. First set up in 2006, it has been revived in 2017 with new leadership. The second development then followed from the first: the setting up the PALIAct Liberation Library in the centre of Nairobi. Vita Books has been involved in both these developments.

The Kenya Liberation Library is an initiative of PALIAct, in partnership with Vita Books and the Mau Mau Research Centre. The need for such a library follows from the fact that progressive literature has over the years been ignored by most institutions — libraries as well as learning institutions. Young people with passion to bring about improvement in the country and thirsty for materials that would inspire them in their quest for social justice get disappointed as such materials are hard to come by. Public and academic libraries have been deprived of funding by government policies and survive mostly on donations from overseas. While many such donations are of good quality material, as for example those donated by institutions such as Book Aid International, they reflect a capitalist worldview and obscure the fact that alternative systems, viewpoints and ideas that may be more relevant to Kenya exist. These remain outside Kenyan boundaries since they are not part of the donated packages.

The few available materials can only be found in bookshops and are too expensive for the majority of the population, especially the youth. The problem is made worse by the fact that most of the bookshops tend to shy away from storing those materials as not many people buy them, concentrating more on fast-moving academic books instead.

In contrast, PALIAct has an initial collection of almost a thousand titles of progressive materials, mostly books but also pamphlets, videos and photographs. It incorporates DTM’s underground library set up by Nazmi Durrani and donated to the Movement on his untimely death by his family. A majority of these are classics are either out of print or cannot be found in the local bookshops. Other material has been donated by the Mau Mau Research Centre, Vita Books and many individuals active in the information struggle in Kenya.

The library is run by a steering committee of five people which ensures teamwork, efficiency, transparency and accountability. Membership is open to all who agree with the vision and Principles of PALIAct. Many contribute their labour, skills, experience or other resources to PALIAct. Members pay an annual fee together with a refundable deposit. Anybody can join the library irrespective of ethnicity, religion, gender, region, race or disability. Membership is open to individuals or to institutions whose members then have access to the material.

The majority of members at present are university students and human rights activists. The library is trying hard to attract workers who are the main target as the main objective of PALIAct is to create a people-orientated information service that can meet the information needs of workers and peasants.

‘I managed to get all books from the Nazmi Durrani Collection that were donated to MKDTM and brought them to PALIAct office. They are in hundreds and I believe they will be of great assistance to members, especially students.’ (Kimani Waweru, email, 7 October 17)

It is hoped community groups can be encouraged to, affiliate, with the library and already there is interest from a number of human rights and social justice organisations from working class areas of Nairobi.

Among the activities which PALIAct undertakes are study group sessions on various topics related to books read by members. The group usually appoints one of the members to lead the discussion. While these are small steps in the context of the needs of the entire nation, significant changes often start with small steps. PALIAct and PALIAct Liberation Library seek to throw some light in the darkness. Vita Books is proud of its association with these initiatives.

SK: What is your view of the weak, sometimes non-existent, library budgets in several sub-Saharan African countries, where many libraries have become dependent on a culture of (usually Northern) book donations? What is the effect of this situation on autonomous/independent publishing?

SD and KW: The problems that PL faces, as discussed above, in Kenya and Africa are the same that libraries, publishers and booksellers face. The neoliberal policies pushed onto Africa by the WTO, World Bank and IMF have had the result of strangling educational and public libraries, turning them into beggars for crumbs from overseas. Their independence is limited and the content of what is published locally also reflects the needs of corporations, not the needs of working people. Bookselling, publishers and libraries in Kenya suffer from artificial controls on demand for books, driven by government policies such as the 16% tax on books, restrictions on recommended books in curricula and restricting diversity in the contents of books. In order to enforce such restrictive practices, the government then restricts funding to school, public and academic libraries thereby creating an artificial vacuum in book sales and availability.

And yet, it is obvious if one visits public and academic libraries or even looks at street booksellers that there is a great hunger for books in general, and particularly for content that reflects more relevant and alternative views and experiences.

There are a number of ways that this situation can be addressed, but an important obstacle has to be overcome first. The economic and political climate created by Kenya’s elite rulers ensures that there are few among educators, librarians and booksellers and publishers who can stand up to challenge government policies in their field. The recent strikes by doctors and nurses saw the full brutal attack by the state apparatus including armed police. There is thus a lack of progressive, transformative leadership in many professions, which suits the ruling classes as they face little challenge.

The priority is to understand the politics of information and communication in Kenya before any meaningful change can be made. The key sectors interested in books, reading and learning are all organised in their own organisations, while actual and potential readers remain outsiders with no power over policies. What is needed is a large national partnership of all these forces to be able to influence government policies. Perhaps setting up a Reading and Learning Partnership can bring together parents, students, publishers, printers, libraries, media and other interested partners, and united they may have power to force meaningful change in government policies. National and regional campaigns to demand increases in allocations for libraries, school and college textbooks can be effective in changing the minds of local and national politicians and showing that their interest lies in heeding these campaigns.

There could be pressure to make compulsory fixed allocations for books for all libraries, schools, colleges and universities that could link up with recommendations from UNESCO, IFLA (International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions) etc. At the same time reading of fiction for pleasure also needs to be emphasised so that the focus is not only on learning material.

Radio stations and newspapers can be more active in promoting reading by running book reviews, and holding book events regularly in community centres – libraries can also help with this. Radio is a particularly important medium as it reaches working classes and peasants, in towns as well as in the countryside. Githaiga (2013) shows the potential that radio and TV have in supporting people’s learning and entertainment, besides improving people’s livelihood:

Radio is the most accessible and affordable broadcasting medium in Kenya. A survey from 2008 revealed that some 7.5 million homes have radios and 3.2 million have television sets. Of the homes with radios, 5.5 million are in rural areas and 1.9 million in towns. Further, 1.8 million television set owners are in rural areas while 1.4 million are in urban centres.

The political situation in October 2017 following two elections provides an opportunity to set a progressive agenda on information, education, libraries and publishing on the national scene. Perhaps a Charter of Information and Learning Rights could be worked out in partnership with working class institutions and progressive people and set before all parties vying for political power as a condition for working people’s votes. This can draw attention away from the divisive politics of ‘tribalism’ and religious ‘divisions’ to issues that affect the lives of working people. Some may oppose such an approach and claim that it takes libraries and publishing into the realm of politics, which librarians, publishers and educationalists do not ‘do’. But if they miss this opportunity now, the doors to change may close for a long time and ‘politics’ will surely ensure that the TINA-approach will drive libraries and publishers into darkness once again, and another opportunity to develop relevant information, education and publishing opportunities will be lost, as happened at the time of Kenya’s independence.

SK: Shiraz, you have also written and published a historical case study of publishing and imperialism in Kenya,1884-1963. Besides the clear message conveyed in the title, Never be Silent, what other conclusions did you draw from this research for the practice and pursuit of publishing in Kenya, and beyond, today?

SD and KW: There have been significant changes in the publishing field in Kenya since independence in 1963 with new publishers, bookshops and other institutions replacing or supplementing the colonial ones. There is, at least on the surface, more freedom to set up publishing firms.

And yet, at another level, the fundamentals have not been addressed. Kenya’s position as a favoured neo-colony in Africa has limited the independence of its publishing sector. While freedom of independent thought and association are enshrined in the constitution, any action which is deemed to be unfavourable to the ruling elite has to be self-censored or is dealt with by armed police and the GSU (General Service Unit) or hired armed thugs sustained by interested parties. Publishers tend to be afraid to tackle ‘difficult’ topics such as the struggle for independence.

At another level, government policies have created inequality in society with the majority of people barely surviving. The main struggle for them is to satisfy the basic needs of food, clothing and shelter. This has dampened effective demand for books. It is not necessarily that people are not interested in reading for study or pleasure; it is a question of resources.

There is insufficient attention being paid to the demand side of book trade. An entirely new mindset is needed to understand and respond to the reality of publishing in Kenya today.

And the key issue is the content of published material. While it was possible in colonial times for Mau Mau to publish over 50 newspapers, publishing such alternative material is not possible today in Kenya, so strong is the grip of the ruling classes on people’s freedom to exchange ideas and experiences. While there is an increase in the volume and print quality of published material, it is the content that has suffered. Little of relevance to working people, who are the majority of Kenyans, is published and distributed.

Yet the availability of social media is forcing change in society. It remains to be seen how this translates into the publishing sector. New forms and content of books and other material can flow directly from such technological changes.

The way forward for professional librarians, information workers, and publishers is not to pretend that they are neutral by not taking sides in the ongoing class struggle in the country. By their inaction, they are taking the side of the ruling classes in maintaining the status quo. Librarians, information workers, publishers, in common with other sectors of the society, need to be part of people’s struggles for liberation. Kenya did not defeat colonialism by being scared of challenging colonialism. Similarly they will not be able to change the status quo by sitting on the fence. History teaches that no system, however oppressive, survives forever. But it needs blows from below in every field before a fairer and just system can develop. Doctors, nurses, teachers and trade unions have pointed the way. Librarians and publishers cannot afford not to join hands with them and working people struggling for liberation in every field of life.

References

Durrani, Shiraz and Elizabeth Smallwood (2006): The Professional is Political: Redefining the Social Role of Public Libraries. Progressive Librarian. No. 27. pp. 3–22. Available at: http://www.progressivelibrariansguild.org/PL/PL27/003.pdf, accessed 9 October 17.

Durrani, Shiraz (2006): The PALIAct story. Information Equality, Africa No. 2 (2006). pp. 7–9. Available at: http://vitabooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2015/03/2._information_equality_africa_issue_2__dec06_e.pdf, accessed 29 September 2017.

Durrani, Shiraz (2008): Information and liberation: Writings on the politics of information and librarianship. Nairobi: Vita Books.

Durrani, Shiraz (2014): Progressive Librarianship: Perspectives from Kenya and Britain, 1979–2010. Nairobi: Vita Books.

Durrani, S. (2016): Politics of Information (pdf). Presentation at a Meeting in Nairobi. Available at: http://vitabooks.co.uk/vita-books/publication-list/durrani-s-2016-politics-of-information-nairobi10-9-16/

Githaiga, Grace: Technological Advancement: New Frontiers for Kenya’s Media? Available at https://www.gp-digital.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Kenya.pdf, accessed 6 November 2017.

Karimi Nduthu, A Life in the Struggle. (1998). Vita Books: London and Mau Mau Research Centre: New York.

Mau Mau Art: Art is the Weapon>. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EWSMxW6CJKI&feature=youtu.be

Pambazuka News, www.pambazuka.org

Prashad, Vijay (2017): Academic arguments backing white supremacy and colonialism are making an ominous comeback. Quartz India. 22 September, available at: https://qz.com/1083767/academic-arguments-backing-white-supremacy-and-colonialism-are-making-an-ominous-comeback/, accessed 23 September 2017.

South African History Online (1965). Available at: http://www.sahistory.org.za accessed 26 September 2017.

Tandon, Yash (2017): Reflections on Kenya: Whose capital, whose state. Pambazuka News. Available at: www.pambazuka.org/democracy-governance/reflections-kenya-whose-capital-whose-state, accessed 26 September 2017.

Younge, Gary (2017): Remember this about Donald Trump. The Guardian.26 September. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/sep/26/donald-trump-nfl-kneeling-national-anthem, accessed 29 September 2017.

[i] Kamusi ya Kiswahili Sanifu (1981): Dar es Salaam: Oxford University Press. This give as an example of ‘vita’: ‘vita via Majimaji – vita vilivyopiganwa mwaka 1905-1907 baina ya wenyeji wa Tanganyika na wakoloni wa Kijerumani’.

[ii] A Standard Swahili-English Dictionary (1955?): Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[iii] Further information on these and other Projects and activities is available at http://vitabooks.co.uk/projects-for-change/paliact/.

[iv] Details of some of the earlier projects are available in the ‘Ideas into Action’ section in Durrani (2008): Information and Liberation: Writings on the Politics of Information and Librarianship, Duluth: Library Juice Press. Available from African Books Collective.

[v] Available at: https://independent.academia.edu/httpvitabookscouk/Analytics/activity/overview, accessed 7 October 17.

[vi] These figures are for all the books include various earlier versions of the publications, including conference presentations on Makhan Singh.

[vii] Views include Vita Books publications as well as other material available on the Vita Books website.

[viii] All quotes are from the book Karimi Nduthu: A Life in the Struggle, 1998, Vita Books/Mau Mau Research Centre.

[ix] Durrani, Shiraz (2008) p. 32.

[x] ibid. pp. 31–32.

[xi] Durrani, Shiraz (2014) p. 118.

[xiii] ibid. pp. 379–81.